Makin Me Look Good Again Genius

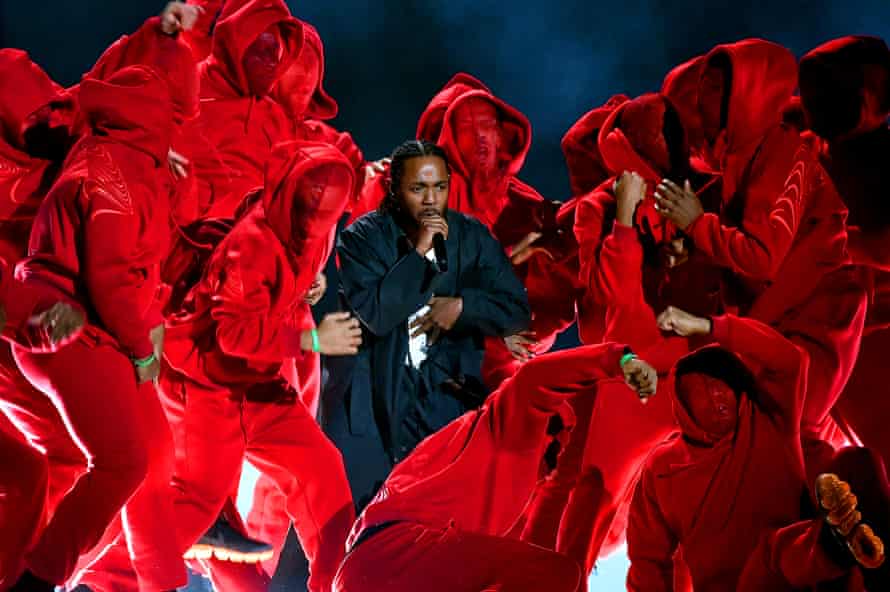

A southward Kendrick Lamar notes on Mr Morale & the Big Steppers' opening track, information technology'southward been 1,855 days since he terminal released an album. By his ain account, the intervening five years have been something of a rollercoaster ride. He and his partner started a family unit (his children are on the anthology's front cover), he made an acclaimed acting debut, performed at the outset ever Super Bowl half-time show centred effectually hip-hop, and watched as the praise for his work shifted into an unprecedented realm. He won the Pulitzer prize for music, becoming not just the kickoff rapper simply the first pop artist flow to receive the accolade.

Equally Mr Morale & the Big Steppers makes clear, he besides struggled with his mental health, sought therapy and endured a ii-year stretch of author's block – cured, he suggests, when he "asked God to speak through me".

Clearly his prayers were answered in no uncertain terms: on the evidence here, the block ended like a dam bursting. The anthology is eighteen tracks and nearly 75 minutes long. Anyone who learned to be wary of rappers who confused quantity with quality in the CD era, when every hip-hop album came stretched out to a disc's maximum playing time, should note that there isn't a moment of padding here.

Mr Morale & the Big Steppers is absolutely crammed with lyrical and musical ideas. Its opening tracks don't and then much play as teem, cutting aimlessly from ane style to another – staccato piano chords and backwards drums; a frantic, jazzy loop with a bass pulsate that recalls a racing heartbeat; a mass of sampled voices; thick 80s-pic-soundtrack synth and trap beats. On Worldwide Steppers, Lamar's words rattle out at such a stride that they threaten to race alee of the bankroll track, a muffled, dense, relentless loop of Nigerian afro-rock band the Funkees that all of a sudden switches to a burst of laidback 70s soul and back again.

On N95, the tone of his delivery changes so dramatically and so frequently that it sounds less like the work of ane man than a series of guest appearances. When it comes to actual guest appearances, information technology casts its net broad – Ghostface Killah, Sampha, Summertime Walker, the singer from Barbadian popular ring Cover Drive – and occasionally delights in some unlikely juxtapositions. I interlude features a string quartet and 74-yr-old German cocky-assist author Eckhart Tolle discussing the perils of a victim mentality alongside Lamar's cousin, rapper Baby Keem, whose concerns are more than earthy: "White panties and minimal condoms".

The anthology keeps executing similar tonal handbrake turns, from deeply troubled to lovestruck and from furious to laugh-out-loud funny, the latter switch covered by We Cry Together, an sick-tempered duet with role player Taylour Paige that drags everything from the rising of Donald Trump and the crimes of Harvey Weinstein to the question of why "R&B bitches don't feature on each other'due south songs" into a heated domestic dispute. Even by hip-hop standards, in that location's a quite phenomenal amount of swearing involved: no one has made more artistic upper-case letter out of 2 people telling each other to fuck off since Peter Cook and Dudley Moore reinvented themselves as Derek and Clive.

Lamar'due south lyrical skill is prodigious enough to make gripping rhymes from some very well-worn topics: simulated news, the projection of imitation lifestyles via social media, the pressures of fame. Just more notable withal is his willingness to accept risks.

Auntie Diaries, a lengthy, heartfelt lobbying on behalf of the trans community, is new territory for mainstream hip-hop. It confesses Lamar'south past homophobia and lashes out at the church and his fellow rappers in dextrous, convincing manner. On Savior, he upbraids popular's censorious moral climate every bit an unthinking exercise in liberal box-ticking. Elsewhere, the rails turns its ire not only on white people glomming on to the Blackness Lives Matter motility ("ane protest for you, 365 for me"), but the black community and indeed himself.

He employs Kodak Black, a rapper whose lengthy legal issues include pleading guilty to assault and bombardment. This guest spot volition exist seen by some as an ethical failing but Lamar seems uninterested in moral purity, and more than in how surroundings and other factors shape behaviour. Tellingly, the next track begins with Tolle: "Let'south say bad things were done to you when y'all were a kid, and you develop a sense of self that is based on the bad things that happened to you lot…"

He saves the album's most shattering moment until the cease. Mother I Sober offers a devastating series of verses that draw together slavery and sexual corruption, and deal unflinchingly with a sexual assault experienced by his mother and an episode in which a immature Lamar, being questioned by his family, denied that a cousin had driveling him. He was not lying but the atheism that greeted his answer, he suggests, led to feelings of inadequacy that left him "chasing manhood" and nearly losing his partner in the process. It's hard just compelling listening, held together by a fragile chorus sung by Portishead's Beth Gibbons.

Before that is a rail chosen Crown, on which a piano seesaws between ii chords and Lamar looks dolefully towards a moment when critical acclaim eludes him and his audience shrinks.

"I tin can't please everybody," he keeps repeating, as if it's a mantra designed to manage his eventual decline. It's smart forward thinking: after all, every successful artist has their unrepeatable moment in the sun and no one's lasts for ever. But, on the evidence of Mr Morale & the Big Steppers, an album that leaves the listener feeling almost punch-drunk at its decision, it's not a mantra Kendrick Lamar has any need of at the moment.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2022/may/13/kendrick-lamar-mr-morale-the-big-steppers-review

0 Response to "Makin Me Look Good Again Genius"

Post a Comment